LOCARNO NITES (SEASON 4, EPISODE 1)

Looking back at the rush of modern filmmaking that was the 2017 edition of the Locarno film festival, through the vantage point of what does a film festival means these days

What stays after a festival’s done? Which films, for better or worse, linger on in our memories long after the event itself has blurred into just another year in the festival’s history?

The question asked itself while I was discussing with an online friend how Katsuya Tomita’s lovely Bangkok Nites never really took off after its competition slot at Locarno 2016. Despite a lot of rave reviews, maybe because of its late showing (at the tail end of the programme), the film left with no prizes and never gained much traction.

But then, neither did that year’s main winner: Bulgarian director Ralitza Petrova’s debut feature Godless, a ruthlessly bleak indictment of post-Soviet failed government, disappeared from the radar almost as much as (if not even more than) Bangkok Nites. None of this is overly important; films are what they are and will continue to be what they are, and juries will be juries, as it all comes down to a circumstantial combination of personal tastes and politics, especially since most festivals (Locarno included) demand that the wealth be spread around so that no film accumulates all the top awards.

Jury awards are, of course, an art of compromise and Locarno 2017 was no different, even if the pool of candidates was actually pretty good. As Godless proves, being a winner is no guarantee of future career; in some cases, like Lav Diaz’s 2014 winner From What Was Before, the whole point can be to provide support and validation for unconventional filmmakers that don’t align with the laws of commerce and marketing. But the economy of the art film business is such that the festival circuit seems to now be a market in and of itself. Sample any festival programme and you’ll get a number of films whose social, formal or artistic preoccupations seem custom-made for festival play rather than to connect with viewers or go on to a proper commercial career.

Godless, to me, was a good example of that; in this year’s official sections, stuff like Andrei Cretulescu’s Charleston, a wry but dullish Frankenstein monster of Greek Weird Wave tropes hand-sown to Romanian New Wave realism, is another. Can a major prize, therefore, still make a difference? It certainly didn’t seem to when it came to Godless. And it’s unlikely to help that much in the case of Chinese master documentarian Wang Bing, this year’s main winner with Mrs. Fang.

Wang’s work has been admired in the worldwide festival circuit ever since his mammoth West of the Tracks showed up out of nowhere back in 2003, and he’s been a fixture at pretty much every major festival since. But his unflinching work has almost become a genre unto itself within the rarefied arthouse/documentary scene, as pretty much no one else is making the kind of pared-down, ascetic, observational, immersive documentary that Wang is specializing in, its approaches occasionally overlapping with mixed-media or museum-cube installation (Mrs. Fang premiered at Kassel’s documenta14, which co-commissioned it, and some of his previous films have also existed as parallel museum exhibits).

In this case, the Golden Leopard is clearly validation for a courageous body of work that must continue to exist, but Mrs. Fang is unlikely to reach many new viewers, particularly taking into account its harrowing subject matter: the final days in the life of a rural villager dying of a form of Alzheimer’s disease. Mrs. Fang lies almost still in her bed waiting for death to arrive, while all around her life goes on; her family is torn between taking care of her, preparing for the funeral ceremonies and leading their own lives as if nothing’s changed.

It’s the exact opposite of intrusive, spurious “human interest”; Wang is trying to give Mrs. Fang a humanity, a dignity that transcends the mere human interest, looking for a flicker of life in the eyes that are her only form of communication with the outside world. Still, this is an experience that requires the viewer to head into the theatre fully committed to what he’s about to see, and previous knowledge of his work is advised. Mrs. Fang isn’t really an entry point for the uninitiated.

On the other hand, my bet is the Special Jury Prize is going to help a lot in the case of The Good Manners, Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra’s entertaining and ambitious horror-socio-musical-fairytale that seems to have been this year’s breakout film in the programme. Simultaneously ambitious and accessible, delightfully derivative and outrageously original, The Good Manners uses Brazilian folk superstitions as a gateway into a literally fractured fairytale that plays like a Disney-gone-Sondheim version of Anna Muylaert’s The Second Mother in modern-day Brazil.

A new (black) live-in nanny with no previous experience is hired by a wealthy (white) pregnant single woman disowned by her family, who behaves oddly every full moon; what comes next makes visible the nature versus nurture debate in a work that is also a clear indictment of the Brazilian class system, where, despite all the hardships, it’s the working class that holds the real key to happiness and a good life (though nobody would misconstrue what Isabel Zuáa’s Clara has to go through as happiness).

The genre aspect of The Good Manners can also be parlayed into a few other entries in the Locarno sidelines: playing in the Piazza Grande open-air screening schedule was French duo Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani’s Let the Corpses Tan, a highly formalist meta-take on 1970s Italian exploitation movies that follows their interest in gialli and Italian horror to a blood-thirsty western-spaghetti disguised as wannabe sun-drenched noir. It’s technically an adaptation of a cult thriller by the French duo of Jean-Patrick Manchette and Jean-Pierre Bastid, where a heist-gone-wrong devolves into a stylized shootout-cum-siege movie. Cattet and Forzani push the period formalism to 100 (solarized main titles, widescreen framing, screen-filling close-ups, burnt-out colours, period score cues) but at some point the film becomes a dazzlingly presented catalogue of tropes, guaranteed to make genre students drool but that might be a little too much for the more casual viewer.

In the same genre lane you will find French outsider auteur F. J. Ossang’s competition entry 9 Fingers, whose retro-futuristic B&W stylings owe as much to classic studio tough guy B-movies as to French graphic novels of the fifties/sixties (I kept thinking of Bob Morane — go figure). It’s a peculiar, oblique variation on the Flying Dutchman trope of the haunted ship, but, though reasonably representative of Ossang’s usual low-budget mash-ups (this is only his fifth feature in 40 years, and all but one of them were shot in B&W), it’s more lethargic and less inspired than his previous work (personally, I like the previous Dharma Guns better). Ossang is an acquired taste whose approach has been limned over the years; his best director award is, again as with Wang, a recognition of a body of work that exists stubbornly on its own, fully outside modern-day standards while yearning for some impossible past.

For my money, I liked better Jan Zabeil’s discreet Piazza Grande companion Three Peaks, which starts off as a mild family drama (a young son of a previous marriage as the third wheel complicating the relation between a separated mum and her new partner), and slowly fades into psychological horror as boyfriend and son find themselves squaring off at each other. Zabeil manages to slowly turn Arian Montgomery’s troubled, confused, petulant boy into some sort of monstrous, selfish child, but Three Peaks seems to pull back from the abyss just as it’s about to leap headlong into it, as if it was lacking the courage of the convictions it seems to toy with. That still leaves us with a handsome, thought-provoking psycho-thriller buoyed by Zabeil’s methodical mise en scène and excellent performances from Montgomery and Alexander Fehling. (Nothing against Bérénice Bejo as the mum, it’s just that her role is rather thankless.)

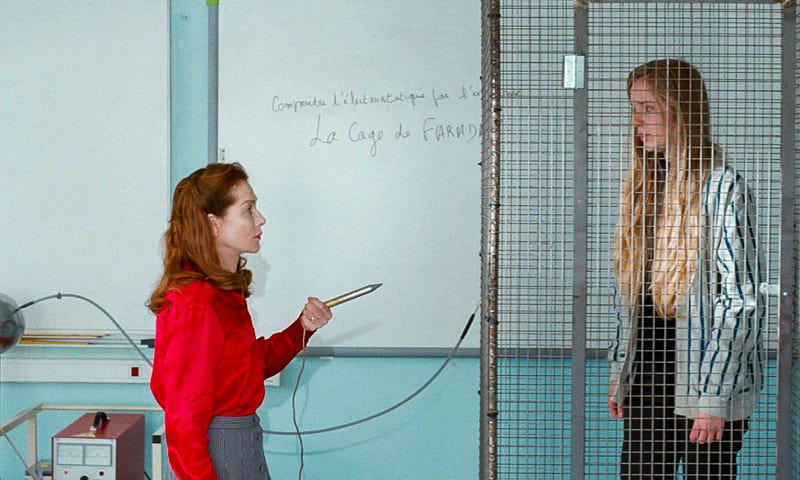

While we’re on the subject of genre: no one will ever deny that any Isabelle Huppert performance is any less than magnificent. And her mousy teacher become woman (literally) on fire in Serge Bozon’s layered Mrs. Hyde, a film I definitely want to revisit outside the festival rhythm, is a particular delight. The genre reference is obvious as Mrs. Hyde is a very loose take on Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but it’s also a corrective to the serious school drama that Laurent Cantet’s The Class brought back into vogue. Bozon’s wry satire of modern education, set in a problem high school in the suburbs, has Huppert loosening up to find her true self with a magnificently modulated performance of discrete physical posture and comedy. Her Best Actress award, while undoubtedly deserved, seemed a safe way to award another idiosyncratic director’s body of work more than a particular film; the general reaction to Mrs. Hyde was muted, the film being one of those head-scratchers festival-goers don’t necessarily know what to think about at first.

It would have been interesting to have on the same awards list Huppert and Harry Dean Stanton — an all-too-obvious shoo-in for the Best Actor award for his lived-in wonderful performance in Lucky, John Carroll Lynch’s low-key seventies-ish character study written by two close friends of the actor specifically for him and inspired by his own life. Instead, though, the male nod went to Jamie Bell lookalike Elliott Hove from Denmark, for his in-your-face anti-social mineworker in Icelandic artist Hlynúr Palmarson’s debut Winter Brothers. This Nordic coming-of-age slash community feud drama was visually interesting but dramatically uncompelling (a bit like a lot of the Icelandic and Scandinavian dramas that have become de rigueur at festivals); why many people liked it but not the Italian entry The Asteroids ended up beyond my understanding, since both films have a lot in common, being soulmates where it comes to unpleasant, sullen, entitled young men raging petulantly at the world.

to be continued…

Comments