WEDDING PRESENTS

on POLICEMAN, THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER, CRUEL STORY OF YOUTH and THE GIRL ON THE MOTORCYCLE

It’s

nice to stand back every now and then from the madness that is the

weekly release schedule. Also because it’s good to revisit stuff

you’ve seen a while ago – you’d be surprised at what best

survives the test of time, or how something that you found throwaway

or weren’t particularly enthusiastic about turns into a time

capsule or benefits from the gift of hindsight.

Some

films only seem to gain stature with time – like Nadav Lapid’s

2011 Policeman,

which

I caught in advance of the Israeli director’s retro at the Vila do

Conde short film festival (whose competition he won two years ago

with his wry 40-minute From

the Diary of a Wedding Photographer).

Policeman,

his first feature, is a game of two halves. First, we follow a couple

of days in the life of a SWAT officer in the Israeli

counter-terrorism police; then, Lapid switches to follow a couple of

days in the life of a radicalized angry young woman, part of a group

of college-age youngsters planning the kidnapping of three

millionaires to protest social inequality in modern Israel.

On

one hand, a silent hyper-macho culture of patriarchal violence sworn

to protect the status

quo;

on the other, a high-minded talkative rebellion against that same

status

quo. The

ironies are constantly visible throughout, and the personal is always

political: the cops don’t make enough money, yet are sworn to

protect those who have all the money and look down on everyone else;

society couldn’t care less about moral stands, and there’s a

whiff of hypocrisy in seeing well-meaning bourgeois kids playing at

being revolutionaries (“revolution is not poetry, it’s prose”

says someone at some point); everything is neatly labeled – cops

are heroes, terrorists are scum, millionaires are above the law,

nobody is really listening to anybody else.

Violence

seems to be the only common language all the characters share in a

society profoundly corrupted by money. Lapid may be talking of his

native country, but his film, shot

in a distant, neutral, quasi-procedural

style,

steers

clear of the Israeli-Palestinian issue and prefers to look within the

fabric of Israeli society, sketching a sense of injustice,

polarization, random chaos that turns

out to be pretty

universal and reflect a lot of what’s going on in our own days (not

only in Israel).

Policeman

articulates questions rather than answer them; though made in 2011,

it talks spookily to 2018 in ways that have gotten more visible with

time.

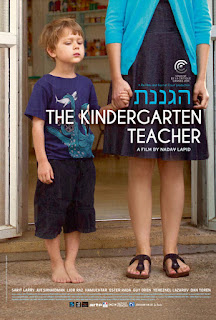

If

Policeman

is uncomfortable, Lapid’s follow-up, 2014’s The

Kindergarten Teacher,

multiplies that by a factor of ten. I can’t say many films have

made me squirm as much in my chair - I felt like I didn’t really

want to be seeing it. This is actually a really good thing: like

Policeman,

The

Kindergarten Teacher

works by upending your expectations of where the film is taking you,

and by making you understand its characters (and by extension all of

Lapid’s characters) are not strange people, outliers, rather

productive

members of society. Nira, the title character, is married happily,

has two grown children, is taking a poetry workshop in her spare

time. But the extent to which something is missing in her apparently

orderly life will only be revealed as she becomes obsessed with one

of her kindergarten wards: Yoav, a young boy of six who will, every

now and then, spit out a perfectly composed, extraordinarily adult

poem, as if in a trance. (Lapid

shoots most of the kid’s scenes with a mobile camera that suggests

the automatic-writing aspect of his creations.)

In

a society where art and poetry are thought of as dilettante pursuits

and where everything is geared towards utilitarianism, survival,

money,

Nira feels it is her duty to protect this delicate, surprising talent

from the assaults of the world – going to extremes that turn out to

be worrisome, if not openly deranged. But Nira does have a point,

even if she belabors and stretches it to breaking point, and Lapid

wants us to

empathize

with a lonely woman who

has

more to give than what

society

is interested in from her.

That’s

why the way she careens into a sort of madness is so well structured

by the director and by his actress, Sarit Larry, becomes so

profoundly uncomfortable to the viewer: it’s as if Nira becomes a

sacrificial victim to the very world she wants to protect the little

poet from, since she’s ultimately the only one who truly cares. But

what is she caring for? Poetry, the

young boy, herself,

her convictions?

The

Kindergarten Teacher

suggests that this sort of self-imposed obsessive slide into

derangement is present in all of us – after all, everyone else in

this film is self-absorbed, only in different ways. It’s not the

individual that is the problem.

In

that, Lapid’s features connect with the late Japanese provocateur

Nagisa Oshima’s second feature, 1960’s Cruel

Story of Youth,

a cautionary tale of young people in love facing a post-war society

that expects them to conform to a box they don’t want to fit in.

Makoto and Shinjio are playing with fire, mostly out of despair and

energy, and the petty larcenies they engage in to survive prey on the

hypocrisies of a Japanese society that hides everything behind a

veneer of decorum. But when you’re in your early twenties decorum

is the last thing in your mind – cynicism, cruelty, nihilism,

naïveté, wanting

everything now,

all

of this is blown

around in our angry young people’s misadventures. Hence

the film’s sumptuous melting-pot of visual shoutouts to the

American rebels-without-a-cause youth melodramas, all strong colours,

widescreen framing and brisk editing.

Yet

there is also a surprising, mysteriously contemporary connection to

the rebellious filmmaking being made in Europe at the time - the

British kitchen sink dramas with their social issues, the stylistic

freedom of French Nouvelle Vague – and an omen

of

the New Hollywood that was still a few years away (I swear I thought

of Malick’s Badlands).

It’s all about standing up for a new approach to storytelling that

takes into account the societal changes taking place.

Still, it’s

important to point out that, even though Cruel

Story of Youth is

formally daring within its context, its narrative construction

remains very much within the constraints of a classic melodrama –

as the story progresses and its plotlines start criss-crossing,

there’s a sense this could almost be Sirkian in its tragic

undertones. But that was part of the appeal of using the same

building blocks to create something entirely new.

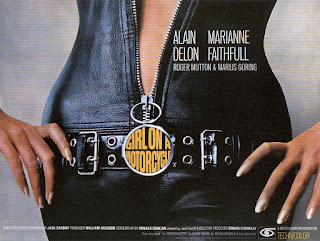

At

the other end of sixties anomie you find the curio that is Jack

Cardiff’s hipster-existentialist The

Girl on the Motorcycle.

Shot at the height of the swinging sixties, it features Marianne

Faithfull at the height of her it-girlness as Rebecca, a bored

housewife who races

from

her home to meet her lover. “Races”

should be taken literally:

the film follows her road trip to Germany astride the glorious

Harley-Davidson that her lover, a sly

philosophy

teacher, gave her as a wedding present.

Adapted

from a 1963 novel by surrealist writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues,

The

Girl on the Motorcycle has

long gone down in history as one of those follies possible only in

the permissiveness of the sixties, made by middle-aged men trying to

catch the young

spirit

of the times. The

stilted construction of its narrative, interspersing Rebecca’s

journey with remembrances in flashback of her love affair, narrated

in her own voiceover, are

scored

by British

MOR

icon Les Reed and shot in wannabe psychedelic flourishes by

Cardiff,

53 at the time of the shoot and

the

ace British DP of Powell & Pressburger’s A

Matter of Life and Death

and The

Red Shoes,

Mankiewicz’s The

Barefoot Contessa or

Huston’s African

Queen.

Seen

today, inside

the

incoherent artsiness of the project lies a truly tantalizing, if

inachieved, meditation on the free will of a modern woman. Like

Nira in The

Kindergarten Teacher or

Makoto in Cruel

Story of Youth, Rebecca

is not content with playing the part of the prim household fairy, she

wants more out of life. It’s disturbing in these days of #MeToo

that, at one point, Rebecca describes herself as “an adulterous

teenage bride… born too soon, a randy bitch permanently in heat”,

as if eroticism and the pleasures of transgressive

sex

would be the only escape routes

available to her.

But

the consideration of a woman’s role in a patriarchal society is all

but undone by the fact that, ultimately, The

Girl on the Motorcycle collapses

into exploitative, peek-a-boo erotica with a hypocritically

cautionary

ending,

saved only by the contradictory perfection of the casting. Faithfull

may have been unable to give her lines any depth, but she looks

positively radiant in full leather as she practically rides her way

into a massive orgasm, mere putty in the hands of the predatorial

Alain Delon, who gets

first billing but is pretty much a supporting role as the

lover with an almost off-handed animal presence. He is the man who

has it all and takes it gladly; she is the woman who gives all of

herself to him. As

far away from the kitchen sink realism of the late fifties, this was

one case of sexual liberation gone awry – yet what might have lain

in store here!

Comments